From the Archives: Artist or Illustrator

Murray Tinkelman, Illustrator, Professor of Art, Syracuse University

January 13, 1962. Private Collection. ©1962 SEPS: Licensed by Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN

In a 1969 interview, Norman Rockwell responded to the question, ”Artist or Illustrator?”

“I call myself an illustrator because my pictures tell a story….Of course, if someone calls me an artist, I don’t argue. Art should

be involved in life … Michelangelo … told stories with his art … the Sistine Chapel is one big story. I don’t put myself in his class but this was illustration – yet nobody calls him an illustrator.”

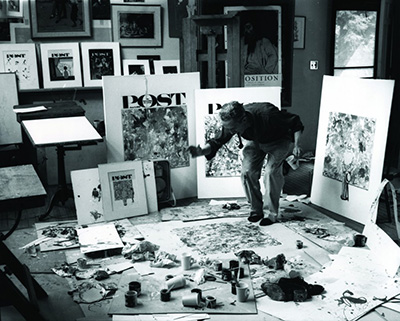

Norman Rockwell reenacts the exact position of Jackson Pollack when Pollack created his 1950 Number 32.

We asked a well-known contemporary illustrator to share his thoughts on this subject with us and here is what he had to say.

The debate is ongoing, “Artist or Illustrator.” What if I pose an alternate question? “Musician or Violinist?” A no-brainer you say? Of course, everyone knows a violinist is a musician. However, it is obvious that not every musician is a violinist. To me, it seems equally obvious that all illustrators are artists, while not all artists are illustrators.

It is not a question of, “Is illustration art?” The question more properly put is, “Can an illustration be art?” To me, the answer is, “Yes, indeed!” Does that mean that all illustration is art? Of course not. The analogies again are clear. Can film be art? Can architecture be art? Of course it can. If Ingmar Bergman directs the film, or Frank Lloyd Wright designs the structure, we have art. In lesser hands, we do not.

That said, we can now move on and ask, “What is an illustration?” Webster’s Dictionary defines illustration as, “a picture or diagram that helps make something clear or attractive:’ That is quite an explanatory definition. However, it might pose as many questions as it answers.

According to Webster and our esteemed Mr. Rockwell, Michelangelo’s frescoes on the Sistine Chapel ceiling or Leonardo Da Vinci’s Last Supper could be classified as illustrations. I respectfully would like to disagree with such a classification. Although those pieces of art indeed fit Webster’s definition, since they both are paintings that make biblical stories clear and attractive, they are, simply, narrative paintings.

An illustrator creates art for reproduction. The intent is paramount. The viewing public sees the reproduction, not the original-the actual painting or drawing done by the illustrator’s hand. A more accurate description of an illustration might be a work of art where the original is the reproduction.

Illustration, as we know it, is as much a product of the Industrial Revolution as it is of the illustrator’s hand. The development of high-speed printing presses and quick drying inks, as well as a transportation system (trains, planes and automobiles) to deliver the published periodicals from coast-to-coast was essential.

These technological advances contributed mightily to the growth of the publishing industry, which became the market and showplace of the illustrator’s art.

The actual painting or drawing created by the illustrator was traditionally considered disposable, and it often was lost, destroyed, or at best, taken home by the employees of the publishers and advertising agencies that commissioned the art. This truly has been a sad fate for an inestimable body of great art.

Now, I would like to discuss what I believe is really the core questionFine Art or Illustration? For decades, the fine art community derided illustration art. The term illustration was used as a pejorative, and Norman Rockwell’s name was used as an adjective rather than a noun to describe any representational imagery, whether it was intended for reproduction or a museum wall.

The schism that exists today between illustration and fine art is really between abstract art and representational art. In the 1950s, when abstract expressionism and the action painters ruled supreme, Andrew Wyeth was tarred with the same brush as Norman Rockwell. Andrew Wyeth was no more an illustrator than Michelangelo or

Da Vinci. He was simply a narrative, representational painter.

The prejudice continues among many painters and critics who are both refugees and disciples of refugees of the 1950s. Now, “times they are a changin'” and there is a ground swell of appreciation for the illustrator’s art in general, and Norman Rockwell’s art in particular.

The recognition of Norman Rockwell’s work accorded by major museums across the country such as the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, the Corcoran Galley of Art in Washington, D. C. , the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City and a wonderful feature article by Michael Kimmelman, art critic of the New York Times, all seem to indicate one thing. Whether or not illustration is high art or low art, it is art.

The comic genius Rube Goldberg, famous for his zany drawings of unnecessarily complex design, once quipped, “I’ve got nothing against Picasso. He works his side of the street and I work mine.”

I would like to quote a dear friend, Jane Eisenstat of Palo Alto, California. Jane is an illustrator, a painter, a writer and an educator. Once, when Jane was asked the difference between a fine artist and an illustrator, Jane replied with a sly grin, “There are no amateur illustrators.”

—Murray Tinkelman

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2001 issue of Portfolio, Norman Rockwell Museum’s magazine for Members