| New Perspectives on Illustration is an engaging weekly series of essays by graduate illustration students at MICA, the Maryland Institute College of Art. Curators Stephanie Plunkett and Joyce K. Schiller have the pleasure of teaching a MICA course exploring the artistic and cultural underpinnings of published imagery through history, and we are pleased to present the findings of our talented students in this weekly blog.Nonsense Illustration by Eduardo –TLaloC- Corral explores illustration as a playful exercise in creative representation, and the ways in which the art form can deceive the uninitiated viewer.

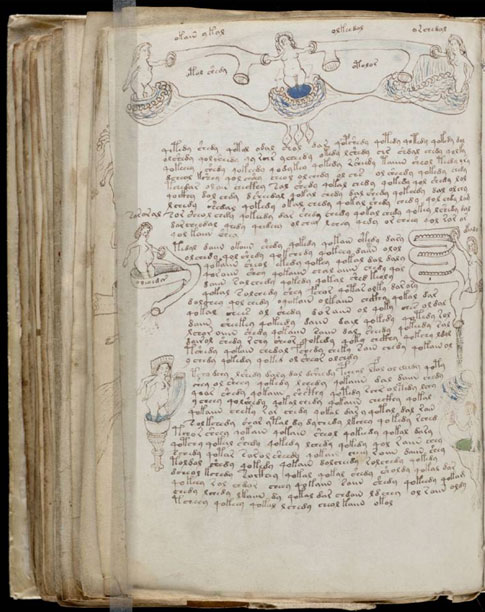

Nonsense Illustration: By Eduardo –TLaloC- Corral Every individual has in itself an inherited fascination with the unfamiliar. It’s an unavoidable part of human behavior and a very peculiar characteristic of its inquisitive nature. Death, ghosts or UFOS, present popular unanswered mysteries that cause us to search relentlessly for answers, but in the end, impossible to get after all, for their ethereal characteristics. But what happen when the mystery or the strange fascination with the unfamiliar relies on a tangible common object like a book? A more important, a book complemented with illustrations? It’s commonly known that a book serves as a conveyer of information on a specific topic. It could be filled with words, symbols, numbers, illustrations, photos or even objects, all put together and collected to archive and give sense to an idea. Having said that, it’s easy to assume that if the information contained in a book is misleading, obscure or even undecipherable, is because that was exactly its purpose from the very beginning. If at the same time the content is complemented by powerful illustrations, the result translates into an automatic sense of mystery. Voynich Manuscript “the world’s most mysterious manuscript” The Voynich manuscript according to Wikipedia: “is a 240 velum page manuscript named after the book dealer Wilfrid Voynich who purchased in 1912. Much of the early history of the book is unknown, though the text and illustrations are all characteristically European. The book resembles herbal manuscripts of the 1500s (possibly from northern Italy), seeming to present illustrations and information about plants and their possible uses for medical purposes. However, most of the plants do not match known species, and the manuscript’s script and language remain unknown and unreadable. According to C14 dating performed by researchers from the university of Arizona the book was made between 1404 and 1438. The authorship of the manuscript remains unknown” (1) .The illustration content of the book implies that are 6 different sections: Herbal, Astronomical, Biological, Cosmological, Pharmaceutical, and finally a segment of recipes. The important question behind this particular collection of contents (6 different), is how “mysterious” this same book could have been without the illustrations that support and imply it’s meaning, only on its undecipherable text? The answer is simple: at least, half as mysterious. The illustrations in the book are what really deliver that sense of mystery and a hint of the yet untold story of these strange symbols. Voynich manuscript w/ images  Voynich cryptic text  Luigi Serafini’s “Codex Seraphinianus” – “The World’s Weirdest Book ever published” If any reader is previously familiarized with its “older brother,” Luigi Serafini’s “Codex Seraphinianus” could be perceived as a tribute to the famous Voynich manuscript, with the significant difference of containing not just its own cryptic language; its contents are taken several levels further from its predecessor by inventing a complete and vast imaginary world and an extensive chapter of unusual flora. Luigi Serafini’s “Codex Seraphinianus” is an illustrated encyclopedia of an imaginary world, created by the Italian artist, architect and industrial designer Luigi Serafini over the course of thirty months, from 1976 to 1978. The book is approximately 360 pages long, written in a strange, generally unintelligible alphabet (2). Divided into eleven chapters, the book is partitioned into two sections. The first section appears to describe the natural world, dealing with flora, fauna, and physics. The second deals with the humanities, the various aspects of human life: clothing, history, cuisine, architecture and so on. In some ways Serafini’s book is very similar to the one from Voynich and viceversa, which makes us wonder if there is a connection on the creative purpose of both artists. So what is the objective of creating a catalogue of an imaginary world of unidentified objects, if the description intended to explain them is written in a cryptic form? Perhaps they were trying to conceal a very well hidden secret behind this strange imagery, but judging for the illustrative contents of both books, it seems that the enigmatic labyrinth that keeps us from knowing the truth, was just an exercise that both artist experimented with for their own gratification. In the end, we can assume that the underlying purpose that tied both artists together their wish to create a language and a world for their own entertainment, that in the end, generated an indirect sense of mystery in the spectator.  As Illustration has evolved through the centuries, it’s easy to understand and interpret its many purposes -from political caricatures that portray social beliefs of a certain era and place, to illustrations generated to document important events in history (like war times) for the lack of photography, or simply images that illustrate products for the consumer. This singular vision of illustration on the other hand seems to focus purely on its visual properties, resulting in a playful exercise for creative representation of images capable of changing it significance, according to the unique interpretation to the viewer. Edward Lear “Nonsense Botany” Finally, it’s important to address the work of Edward Lear, not because he seemed to coincidentally be interested in creating a great collection of imaginary botanical illustrations, as our previous artists, but for being the author who gave a very accurate name of this unique concept of illustration. “Nonsense.” Its interesting to note that even if he didn’t created his own script or language made out of strange symbols, as our previous authors, he created his “Nonsense” illustration based on the way he constructed and popularized his poetry. So it can be concluded that language was a determinant catalyst for creating imaginary worlds, and a powerful tool that gave shape to complex ideas, free from any conventional approach to illustration.  “Nonsense illustration” in the end, has to be the most accurate word to describe this particular kind of illustration, as it suggests a playful exercise that consists mainly of the depiction of images without any restraints, allowing the viewer an open interpretation of its content. Illustration created only with the purpose to construct imaginary worlds from its foundations. Nonsense artifacts, cryptic languages from lost cultures, inexistent civilizations, treasure maps with unidentified topography, invisible entities or unknown creatures ready to open a small window to a latent fictitious universe, eager to grow and defy the perception of what people know and blindly embrace as reality.

End Notes 1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voynich_manuscript 2. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex_Seraphinianus 3. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Lear

Bibliography -“Voynich Manuscript.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 12 Oct. 2012. Web. 10 Dec. 2012. -http://awesta.sibirjak.ru/files/Voynich.pdf -“Codex Seraphinianus.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 12 Sept. 2012. Web. 10 Dec. 2012. -“Nonsense Botany 1871.” Edward Lear, Nonsense Botany 1871. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2012. -“Edward Lear.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 12 Sept. 2012. Web. 11 Dec. 2012. |