| New Perspectives on Illustration is an engaging weekly series of essays by graduate illustration students at MICA, the Maryland Institute College of Art. Curators Stephanie Plunkett and Joyce K. Schiller have the pleasure of teaching a MICA course exploring the artistic and cultural underpinnings of published imagery through history, and we are pleased to present the findings of our talented students in this weekly blog.

Words and Images in Children’s Picture Books by Lynn Chen examines the influence that illustrated picture books have on shaping children’s perceptions of the world around them. Imagination Interacts with Text Since the very first picture book for children called Orbis Pictus came out in 1658, children’s picture books have had a significant place in children’s early education. Children develop their understanding of others by observing their surroundings. An illustrator’s choices of line, color, and shape from which they compose their images are chosen, in part, to attract children’s attention, and help them expand their imagination from the text and images of a story. Relationship Between Words and Images

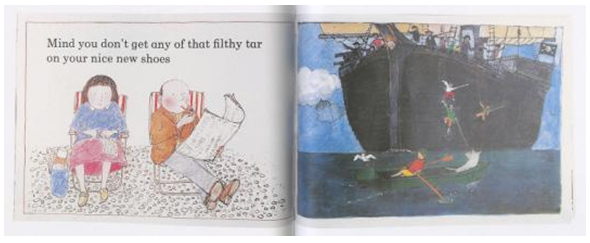

The other interaction is called enhancing interaction, which means the illustrations provide more in-depth explanations than the words. The images and text still work together to create a picture book; in fact, they actually interact more effectively to present a fuller meaning of a story (Nikolajeva & Scott, 226) One example is Satoshi Kitamura’s children’s picture book entitled Lily Takes a Walk. The story tells a simple tale about a girl who walks alone, but she doesn’t feel afraid, because she believes her dog will protect her. In this page, the text demonstrates Lily’s position and the bright light in front of her. Kitamura painstakingly developed the content to show all kinds of details. Besides the lights and buildings in front of Lily, Kitamura also illustrates lots of monsters that pop up at the corner, expressing Lily’s fears that her dog protects her from. Actually, none of these creatures on the recto page is mentioned in the text. However, without the illustration to expand the words, the messages of imagination and fear in Lily’s mind will never be fully delivered to the audience. Those creatures that are never mentioned in the text help to fully express the meaning of text. As mentioned in Children’s Picture Books, “Fabulous artwork can be admired, but if the words don’t interact with the pictures in interesting ways, the book as a whole will not be a success. On the other hand, the written text may be superb but if the pictures are bland the overall effect will be mediocre” (Salisbury, Styles, Alemagna, Smy, and Ida Riveros, 89).  Extra Information Beyond the Words Here is another example from John Burningham, who is an English author and illustrator of children’s book. His picture book Come Away From the Water, Shirley is the story about a little girl who goes on an adventure while her parents take a nap on the beach. Of course the adventure is only in her imagination. In this book, the left page reveals her parents’ world, and all the words are her parents talking and their warnings to her; on the right page is a completely different world, one that portrays the girl’s imaginative world. If Burningham didn’t illustrate Shirley’s imaginative world, the story would be boring and nonsensical. This is perfect example of how the illustration completes the story. There is also another way for illustrators to apply their imagination to images, and to make pictures more attractive to the audience: Some illustrators like to add more details or small elements to fill in the picture, such as a rabbit, a dog, or some tiny mice. Here is an image that best addresses this method. The text for this image is quite simple: “Jack, … sleeping in.” But besides the main character, the illustrator also adds several mice. In fact, introducing some tiny animals into the image is quite common in children’s picture books, for such an addition helps to bring the story to life.

John Burningham

Come Away From the Water, Shirley, 1977

The interesting thing is this: if the mice are taken away, the meaning of the story still seems visually complete. So these animals serve as extra information in the image. Since they have nothing to do with the words, why would an illustrator add these characters? There are two reasons. The first one is because those animals are actually part of our daily life. According to their personal life experience and style preferences, illustrators apply them to the image. It helps to engage the audience and to bring the image to life. Another reason is that sometimes these extra characters help to adjust the composition and even guide the viewer’s eye. An example is the image on the right. Ezra Jack Keats utilizes the dog beside the box and parrot up on the window to guide the audience to the focal point. It is very successful. Conclusion

Bibliography Anderson, Cheri Louise. Children’s Interpretations of Illustrations and Written Language in Picture Books. n.p.: Dissertation Abstracts International, 1998. Art Full Text (H.W. Wilson). Web. 12 Dec. 2012. Benes, Rebecca C. Native American picture books of change: the art of historic Kitamura, Satoshi. Lily Takes a Walk. New York: Dutton, 1987. Print. Keats, Ezra Jack. A Letter to Amy. New York: Harper & Row, 1968. Print. Nodelman, Perry. Words about Pictures: The Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books. Athens, GA: University of Georgia, 1988. Print. Nikolajeva, Maria, and Carole Scott. How Picture Books Work. New York: Garland, 2001. Print. Nahson, Claudia J., Ezra Jack. Keats, and Maurice Berger. The Snowy Day and the Art of Ezra Jack Keats. New York: Jewish Museum, under the Auspices of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 2011. Print. Mayer, Mercer. There’s an Alligator under My Bed. New York: Dial for Young Readers, 1987. Print. Salisbury, Martin, Morag Styles, Béatrice Alemagna, Pam Smy, and Ida Riveros. Children’s Picturebooks: The Art of Visual Storytelling. London: Laurence King Pub., 2012. Print. Salisbury, Martin. Play Pen: New Children’s Book Illustration. London: Laurence King, 2007. Print. Hauppauge, NY: Barron’s Educational Series, 2004. Print. “Word and Image in Fiction.” Word and Image. n.p., n.d. Web. 12 Dec. 2012. |