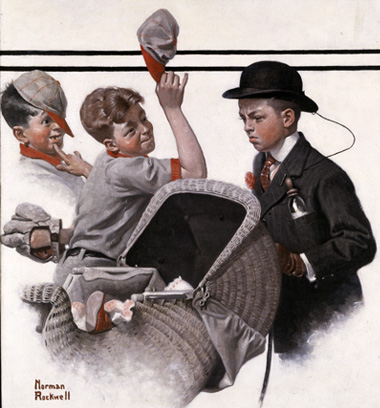

Billy Paine was one of Rockwell's favorite child models, and he posed for all three characters in Boy with Baby Carriage. In a 1920 interview Rockwell said, "I used him on my first cover and he is absolutely a wonder. He has posed five years and is a dandy little actor; he understands moods and expressions no matter how complicated."

Numerous interviews describe Rockwell's memory of Billy Paine as a practical joker. "One day," said Rockwell "he suddenly began yelling for help in a high-pitched voice. Almost at once a policeman flung open the door. Billy had seen the policeman going past and wanted to liven things up a bit."

This was Rockwell's very first Post cover, for which he was paid $75. He wrote, "In those days the cover of the Post was the greatest show window in America for an illustrator. If you did a cover for the Post you had arrived. . . . Two million subscribers and then their wives, sons, daughters, aunts, uncles, friends. Wow! All looking at my cover."

This is one of many covers where Rockwell used children to address a wide-spread masculine anxiety frequently discussed in the national press. Many in the middle-class feared a general effeminization of American life and culture. The anxiety was prompted by a series of social, cultural, and economic shifts that challenged traditional masculine authority. The closing of the frontier, the women's movement, and the growth of urban, corporate life, for example, were perceived as threats to patriarchal power.